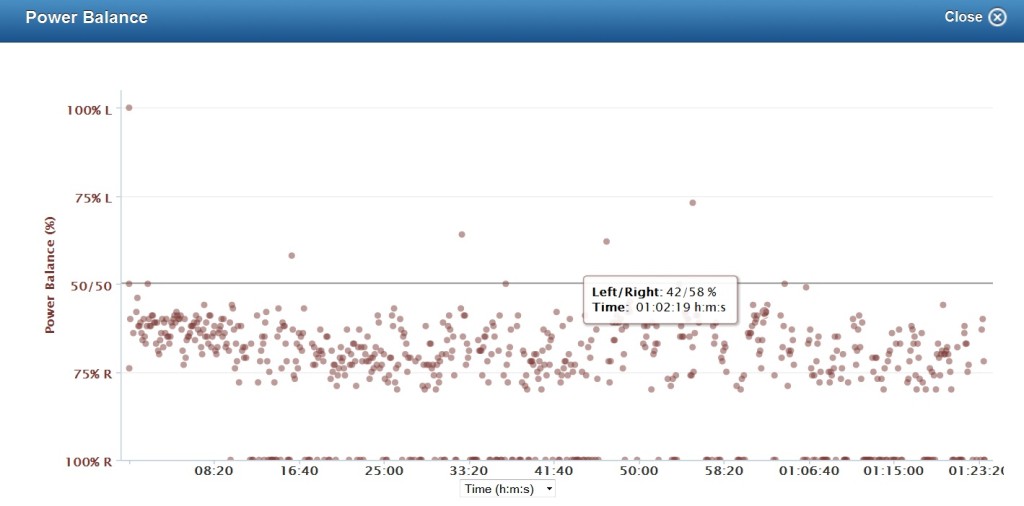

When we last talked, the Garmin Vector pedals were telling me that I had Mark Cavendish’s right leg, and Louison Bobet’s left leg (he’s dead, by the way).

So I had some calibration and familiarization issues. In the end they were easily resolved. Getting these things working comes down to five simple steps…

1. Make sure your cranks are not too wide or too deep so that the pedals fit. Do this before you buy the pedals! (Adapters for wider/deeper cranks are in development).

2. Torque your pedals tightly enough and with at least one washer in place between the pods and the crank arms. This is best done with a proper torque wrench but I am still doing it with a normal pedal spanner. Vector pedal owners everywhere have been purchasing the correct “crow foot” attachment in their droves. That means that they are as rare as World Series tickets (I am a Seattle Mariners fan – we have never been to a world series – that makes those tickets very rare indeed). I expect the crow foot any day. The Mariners in the world series may take a little longer.

3. Get your cycle computer ready - you must adjust the display fields to include Power (I recommend the 3 sec rolling average). Adjust the bike settings to tell the computer that an ANT+ Power device is present. Remember to set your crank lengths correctly.

4. The pedals need to then “find their angle” – i.e. to discover how they are set in absolute and relative terms. This is NOT a calibration but simply a way the pedals get to know their orientation. Most of the Garmin computers other than the Edge500 will take you through this. If, like me and many others, you have an Edge500 then you just get on the bike and ride at about 80 rpm and once a power reading appears then you are all set. You only need do this when you adjust the pedals torque, or move them between bikes, or update their software, or take the batteries out. Once you have done it, switch your computer off and on again.

5. Perform a “Static Calibration” – i.e. your computer will ask, or you can ask it, to perform a calibration where you simply leave the bike motionless and the pedals with nothing touching them. The calibration will take about 5 seconds. Then get on your bike and ride. You can perform an extra calibration by pedaling backwards seven or eight times as you ride. This simply increases the accuracy a little. You can do that at any point in the ride. Your computer will let you know when you have completed this extra step.

So, once I had done all those things in the correct order it was time for me to clear off to Europe on business and not ride the bike at all.   I did get a couple of rides in I suppose. Just tootling around. I recommend NOT being transfixed by the power numbers during the ride – especially at this point. Simply do your normal thing and then upload the data into Strava and/or Garmin Connect and then look at how the power, cadence, HR, etc. seem. You will begin to get a sense of your normal power profile.

If you want to know all there is to know about training with Power you can buy the “Bible” by Allen & Coggan

But let’s get down to business – how were my numbers?

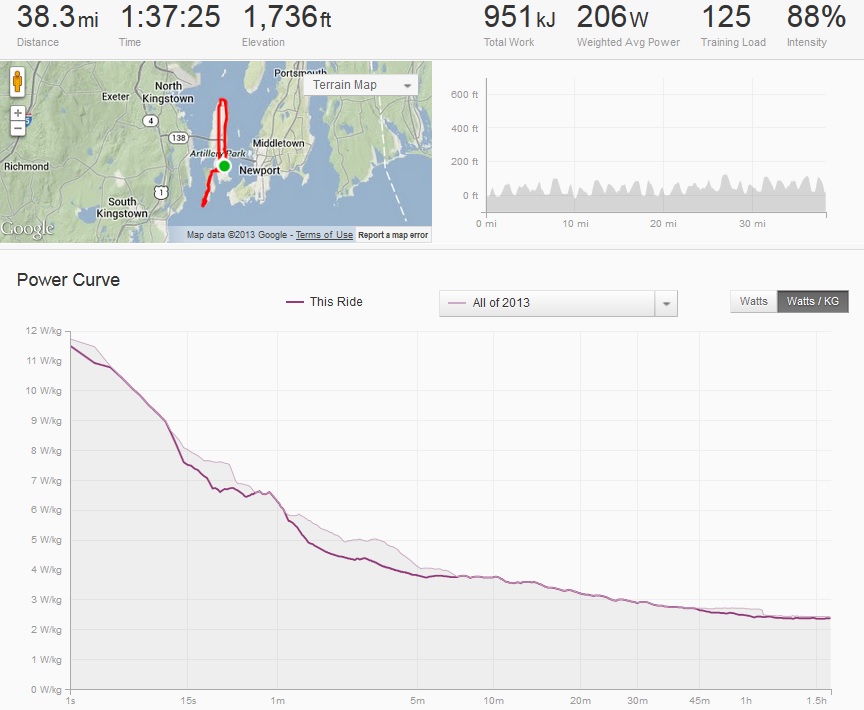

Before buying the pedals, I had estimated my Functional Threshold Power to be about 240W based on a climb I did in Colorado (Lookout Mountain). Just over 30mins for this steady cat2 climb. Using the weight filters on Strava I could look at people who had climbed at a similar speed and who are the same size and who measure actual power. This figure is (240/68)=3.53W/kg and places me at the top end of cat4 and bottom end of cat3 on this very helpful, though somewhat dispiriting, chart that the experts have put together. That seems about right for me.

In practice that means I should be able to ride at that power level for about 60mins if I really push myself. That FTP number becomes one of the key anchors for both training, and the measurement of concrete improvement, for the next year. However, at this stage of my season everything is winding down and I am in the post-season transition/rest phase before starting to Build again from November 1st. (OK so there are some CX races but at the risk of being stripped of my Cycle Lodge kit forever I don’t take CX seriously, and it shows!)

There was the wonderful Jamestown Classic on Columbus Day, however. This gave a chance to see what I was really doing in a race situation. It is a 38mile race (2 x 19mile laps of Jamestown Island) with a couple of little lumps and one stiffer power climb just before the downhill finish sprint. This video from the 2012 edition that we put together gives you a sense of the race.

It usually finishes in a sprint from a slightly-reduced peloton. The plan this year (since I was the only Cycle Lodge rider) was to sit in, go across to anything dangerous, but save energy for a kick over the top of the last climb and down to the finishing line – about a 2 minute effort – since I am not a sprinter.

It didn’t pan out like that – I spent about 10mins off the front solo on the first lap with a maximum lead of around 20 seconds. Moderating my effort so that I was working hard, but not risking blowing up, I averaged 250W for 10 minutes before being swallowed up again. I really hoped a couple of the big teams (Blue Hills, Bikeworks, Threshold, FitWerx) would bridge some riders across – with their help and with their large numbers of team mates blocking behind a breakaway could succeed for once. But it was not to be. Embarrassingly, this relatively weak effort was the most anyone was able to distance the bunch by. We cat4s like to follow each other around like children chasing a soccer ball around the school yard.

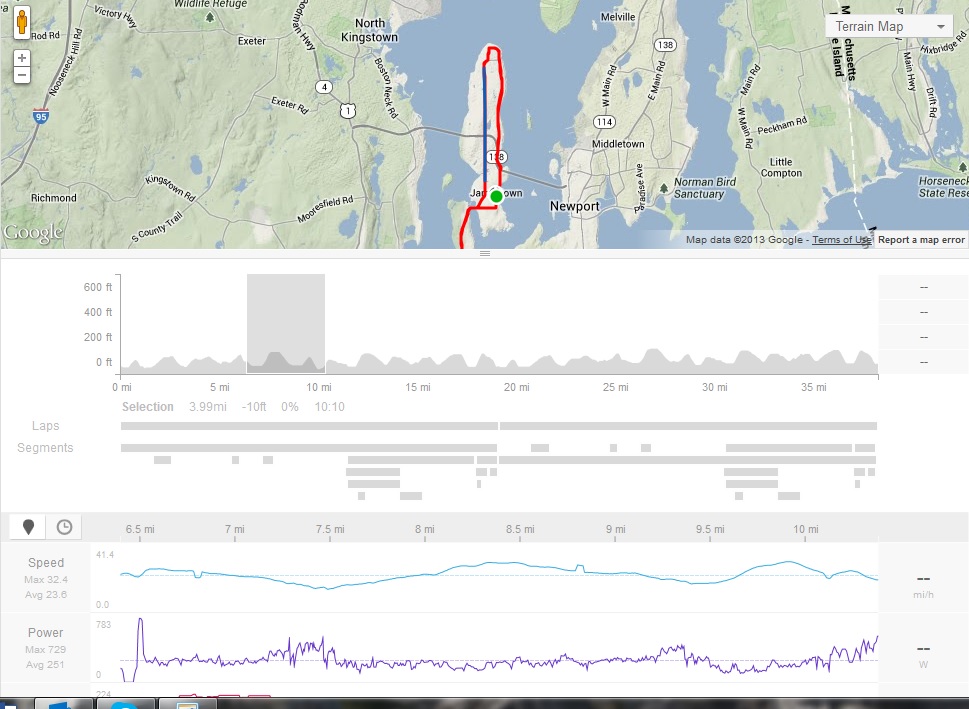

You can see the initial kick on the left of the power line and then I found a decent rhythm. So, in hindsight I did all the right things (I could, maybe should, have pushed a bit harder initially to prompt a proper counter move) but the tactics just didn’t work out for me.

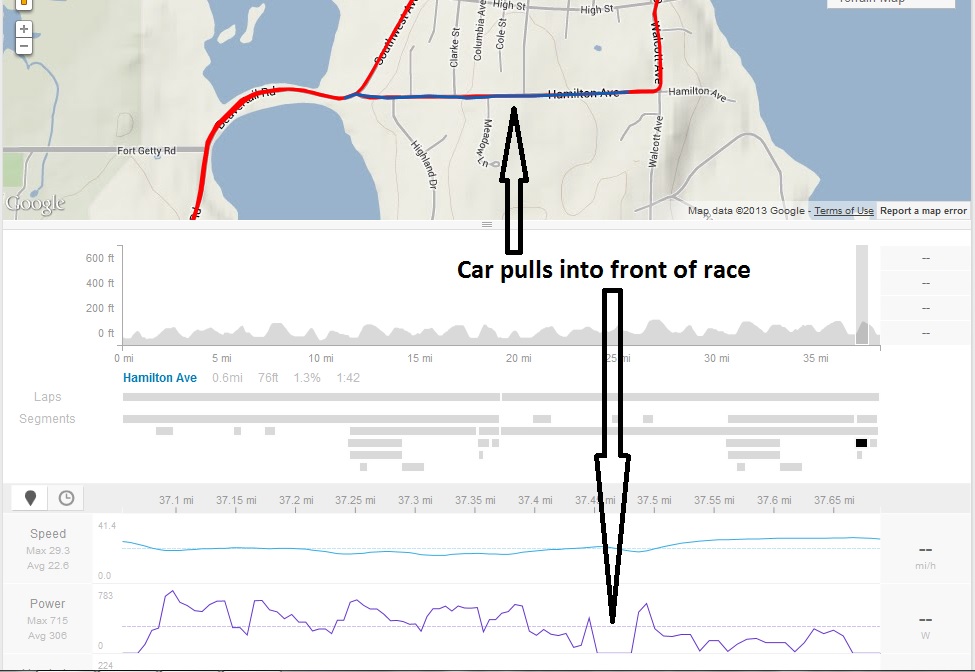

I sat in most of the rest of the race. Last year I approached the finish climb right at the front of the race as my job was to keep it fast for Nick Sousa. This year I ended up stranded a little further back (top 20) coming into the climb. Towards the top a car pulled out between the pace car and the front of the race, then decided to stop dead in the middle of the road. You can see all of this on the power chart below.

The riders braked, then squeezed left and right of the car. I was coming up the inside, and got squeezed into the curb before we were back on our way. Already the chance of the win was long gone and with the squirrelly nature of Cat4 group finishes here I just rode in.

So under normal circumstances we have the great hard-luck story. “I coulda won that race but, ya know, the car pulled out in front of us right before I was going to smoke everyone”.

The power data shows a different truth. I was lazy.

I was lazy allowing myself to sit further back than I should have coming into the base of the climb. Last year with the motivation to ride for Nick I was making damn sure that I was in the right place. This year I was lazy. Mark Roman of Blue Hills pushed and shoved his way to the front with team-mate Jonathan Doller who led him out and he finished 2nd – they had the right plan and executed it. I was lazy and followed wheels.

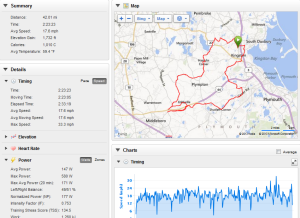

I was lazy on the climb. I picked my way through, but the power data shows a 430W average – a pretty weak effort with some spells below 300W. Compared to last year this was a pretty pathetic attempt. I am fitter this year and I didn’t execute with intent. In fact if you look at the overall race summary below you can see that the race power numbers were not much different to the best power numbers that I executed with the pedals in a couple of easy training rides.

My 5 minute power is mid cat4. My 1 minute power is cat5. My 5 second power is so low that it does not even go on the ranking chart.

What to make of all of this? Some of you may find the whole numbers thing fascinating like I do – a firm way to hold yourself accountable for both your training rides and then your in-race performances. It also shows how “easy” some races can be. My average power (including all the time at zero) was only 180W. Now I got popped 8miles into this race 2 years ago. And this year, from 70ish starters only 35 or so finished on “same time” as the winner. So it’s not “easy” – but once you are at a certain level of fitness, it is clear that races like this are won or lost in the moments of intensity, or through repeated bouts of intensity that wear people down.

Some of you will (rightly) think that this is just another excuse for someone to wax on about their favorite subject (themselves, of course) and waste another few megabytes on the internet.

But the wider point is this – if you want to invest in power measurement there are great rewards to be had. That investment has always been pricy. And it has been difficult to move equipment around between bikes. These Garmin Vector pedals solve that problem. And I love them. I just wish I could have the last 5 minutes of that race to do over. Someone needs to invent a machine to do that.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks